Introduction

Recent developments of CRISPR-Cas9 based homing endonuclease gene drive systems, either for the suppression or replacement of mosquito populations, have generated much interest in their use for control of mosquito-borne diseases (such as dengue, malaria, Chikungunya and Zika). This is because genetic control of pathogen transmission may complement or even substitute traditional vector-control interventions, which have had limited success in bringing the spread of these diseases to a halt.

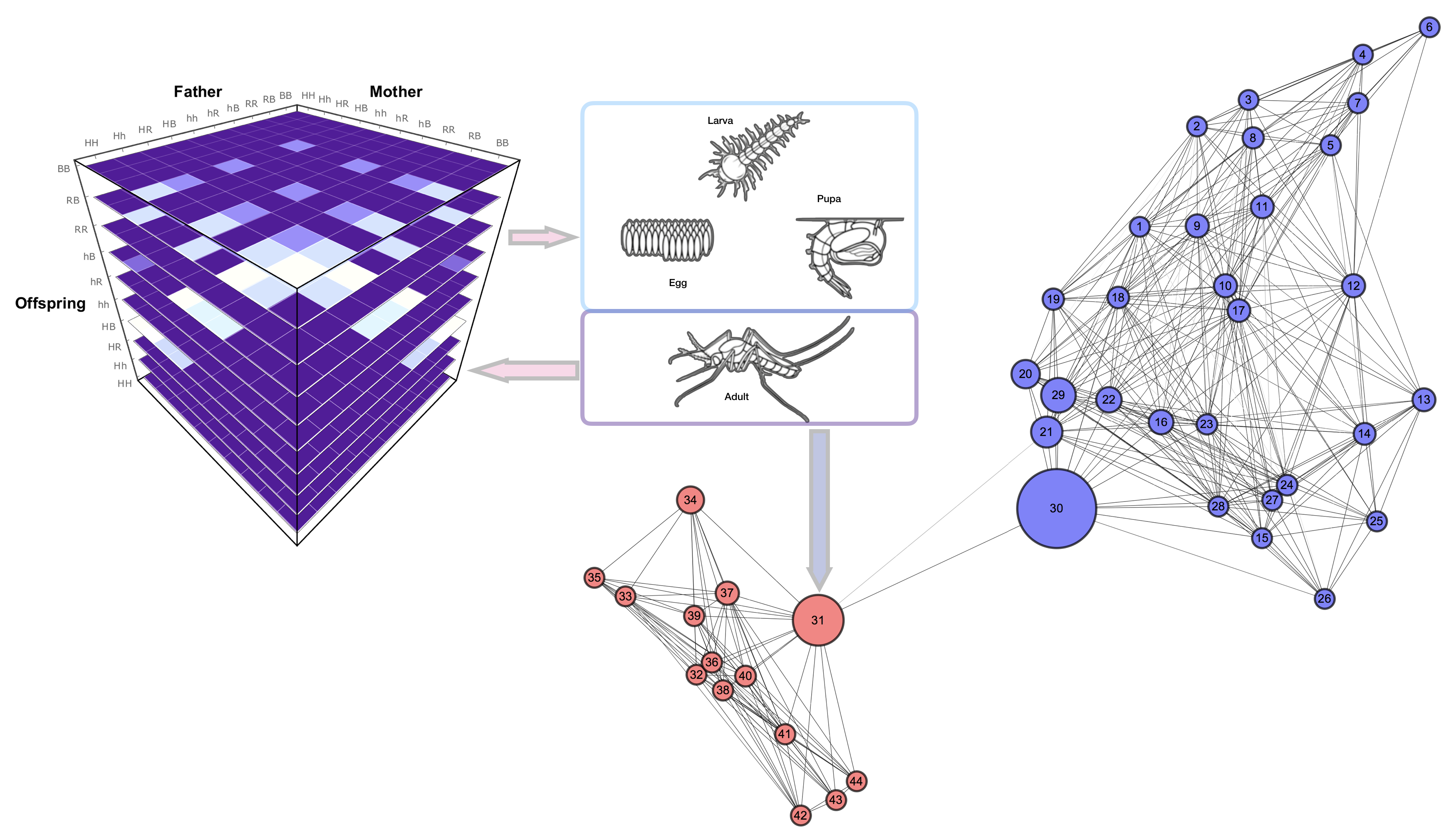

Despite excitement for the use of gene drives for mosquito control, current modeling efforts have analyzed only a handful of these new approaches (usually studying just one per framework). Moreover, these models usually consider well-mixed populations with no explicit spatial dynamics. To this end, we are developing MGDrivE (Mosquito Gene DRIVe Explorer), in cooperation with the ‘UCI Malaria Elimination Initiative’, as a flexible modeling framework to evaluate a variety of drive systems in spatial networks of mosquito populations. This framework provides a reliable testbed to evaluate and optimize the efficacy of gene drive mosquito releases. What separates MGDrivE from other models is the incorporation of mathematical and computational mechanisms to simulate a wide array of inheritance-based technologies within the same, coherent set of equations.

We do this by treating the population dynamics, genetic inheritance operations, and migration between habitats as separate processes coupled together through the use of mathematical tensor operations. This way we can conveniently swap inheritance patterns whilst still making use of the same set of population dynamics equations. This is a crucial advantage of our system, as it allows other research groups to test their ideas without developing new models and without the need to spend time adapting other frameworks to suit their needs.

Brief Description

MGDrivE is based on the idea that we can decouple the genotype inheritance process from the population dynamics equations. This allows the system to be treated and developed in three semi-independent modules that come together to form the system.

Fig. 1: MGDrivE Conceptual Model Framework

Previous Work:

The original version of this model was based on work by Deredec et al. (2011) and Hancock & Godfray (2007), and adapted to accommodate CRISPR homing dynamics in a previous publication by our team (Marshall et al. 2017). As described, we extended this framework to be able to handle a variable number of genotypes, and migration across spatial scenarios. We did this by adapting the equations to work in a tensor-oriented manner, where each genotype can have different processes affecting their particular strain (death rates, mating fitness, sex-ratio bias, et cetera).

Notation and Conventions

Before beginning the full description of the model we will define some of the conventions we followed for the notation of the written description of the system.

- Overlines are used to denote the dimension of a tensor

- Subscript brackets are used to indicate an element in time. For example: \(L_{[t-1]}\) is the larval population at time: \(t-1\).

- Parentheses are used to indicate the parameter(s) of a function. For example: \(\overline{O(T_{e}+T_{l})}\) represents the function \(O\) evaluated with the parameter: \(T_{e}+T_{l}\)

- Matrices follow a ‘row-first’ indexing order (\(i\): row, \(j\): column)

In the case of one dimensional tensors, each slot represents a genotype of the population. For example, the male population is stored in the following way: \[ \overline{Am} = \left(\begin{array}{c} g_1 \\ g_2 \\ g_3 \\ \vdots \\ g_n \end{array}\right) _{i} \]

All the processes that affect mosquitoes in a genotype-specific way are defined and stored in this way within the framework.

There are two tensors of squared dimensionality in the model: the adult females matrix, and the genotype-specific male-mating ability, \(\overline{\overline{\eta}}\). In the case of the former, the rows represent the females’ genotype, whilst the columns represent the genotype of the male they mated with: \[ \overline{\overline{Af}} = \left(\begin{array}{ccccc} g_{11} & g_{12} & g_{13} & \cdots & g_{1n}\\ g_{21} & g_{22} & g_{23} & \cdots & g_{2n}\\ g_{31} & g_{32} & g_{33} & \cdots & g_{3n}\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ g_{n1} & g_{n2} & g_{n3} & \cdots & g_{nn} \end{array}\right) _{ij} \]

The genotype-specific male-mating ability, on the other hand, stores the mothers’ genotype in the rows, the male mate genotype as columns, and each value indicates the ability of a specific male genotype to mate with a specific female genotype. This allows assortative mating to be modeled.

Mathematical Framework

Inheritance Cube

To model an arbitrary number of genotypes efficiently in the same mathematical framework we use a 3-dimensional array structure (cube) where each axis represents the following information:

- x: female adult mate genotype

- y: male adult mate genotype

- z: proportion of the offspring that inherits a given genotype (slice)

The cube structure gives us the flexibility to apply tensor operations to the elements within our equations, so that we can calculate the stratified population dynamics rapidly; and within a readable, flexible computational framework. This becomes apparent when we define the equation we use for the computation of eggs laid at any given point in time:

\[ \overline{O(T_x)} = \sum_{j=1}^{n} \Bigg( \bigg( (\beta*\overline{s} * \overline{ \overline{Af_{[t-T_x]}}}) * \overline{\overline{\overline{Ih}}} \bigg) * \Lambda \Bigg)^{\top}_{ij} \]

In this equation, the matrix containing the number of mated adult females \((\overline{\overline{Af}})\) is multiplied element-wise with each one of the layers containing the eggs genotypes proportions expected from this cross \((\overline{\overline{\overline{Ih}}})\).

The resulting matrix is then multiplied by a binary ‘viability mask’ \((\Lambda)\) that filters out female-parent to offspring genetic combinations that are not viable due to biological impediments (such as cytoplasmic incompatibility).

The summation of the transposed resulting matrix returns us the total fraction of eggs resulting from all the male to female genotype crosses (\(\overline{O(T_x)}\)).

Note: For inheritance operations to be consistent within the framework the summation of each element in the z-axis (this is, the proportions of each one of the offspring’s genotypes) must be equal to one.

Drive-specific Cubes

An inheritance cube in an array object that specifies inheritance probabilities (offspring genotype probability) stratified by male and female parent genotypes. MGDrivE provides the following cubes to model different gene drive systems:

- 1 Locus Maternal-Toxin/Zygotic-Antidote System

- 2 Locus Maternal-Toxin/Zygotic-Antidote System

- Allele Sail

- Split Drive with Parental-Specific Impacts

- DsX-based Cleave and Rescue (ClvR) - Akbari Lab

- X-Linked Cleave and Rescue (ClvR)

- 1 Locus Cleave and Rescue (ClvR)

- 2 Locus Cleave and Rescue (ClvR)

- 2 Locus Confinable Homing

- X-Linked Confinable Homing

- Homing Drive with 1 Resistance Allele

- CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) with 2 Resistance Alleles and Maternal Deposition

- Small-Molecule Induced CRISPR

- X-Linked CRISPR

- Autosomal ECHACR

- X-Linked ECHACR

- Autosomal Immunizing Reversal System

- X-Linked Autosomal Immunizing Reversal System

- Killer-Rescue System

- MEDEA (Maternal Effect Dominant Embryonic Arrest)

- Reciprocal Translocations

- RIDL (Release of Insects with Dominant Lethality)

- Autosomal X-Shredder

- Y-Linked X-Shredder

- Mendelian

- Autosomal Split-Drive

- X-Linked Split-Drive

- Y-Linked Split-Drive

- trans-Complementing Gene Drive

- X-Linked trans-Complementing Gene Drive

- Wolbachia

Population Dynamics

During the three aquatic stages, a density-independent mortality process takes place at each stage (st): \[ \theta_{st}=(1-\mu_{st})^{T_{st}} \] Along with a density dependent process dependent on the number of larvae in the environment: \[ F(L[t])=\Bigg(\frac{\alpha}{\alpha+\sum{\overline{L[t]}}}\Bigg)^{1/T_l} \] where \(\alpha\) represents the strength of the density-dependent process. This parameter is calculated with: \[ \alpha=\Bigg( \frac{1/2 * \beta * \theta_e * Ad_{eq}}{R_m-1} \Bigg) * \Bigg( \frac{1-(\theta_l / R_m)}{1-(\theta_l / R_m)^{1/T_l}} \Bigg) \] in which \(\beta\) is the species’ fertility in the absence of gene-drive, \(Ad_{eq}\) is the adult mosquito population equilibrium size, and \(R_{m}\) is the population growth in the absence of density-dependent mortality. This population growth is calculated with the average generation time (\(g\)), the adult mortality rate (\(\mu_{ad}\)), and the daily population growth rate (\(r_{m}\)): \[ g=T_{e}+T_{l}+T_{p}+\frac{1}{\mu_{ad}}\\R_{m}=(r_{m})^{g} \]

Larval Stages

The computation of the larval stage in the population is crucial to the model because the density dependent processes necessary for equilibrium trajectories occur here. This calculation is performed with the following equation: \[ D(\theta_l,T_x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \theta_{l[0]}^{'}=\theta_l & \quad i = 0 \\ \theta_{l[i+1]}^{'} = \theta_{l[i]}^{'} *F(\overline{L_{[t-i-T_x]}}) & \quad i \leq T_l \end{array} \right. \]

In addition to this, we need the larval mortality (\(\mu_{l}\)): \[ %L_{eq}=&\alpha*\lfloor R_{m} -1\rfloor %& \mu_{l}=1-\Bigg( \frac{R_{m} * \mu_{ad}}{1/2 * \beta * (1-\mu_{m})} \Bigg)^{\frac{1}{T_{e}+T_{l}+T_{p}}} \]

With these mortality processes, we are now able to calculate the larval population: \[ \overline{L_{[t]}}= \overline{L_{[t-1]}} * (1-\mu_{l}) * F(\overline{L_{[t-1]})}\\ +\overline{O(T_{e})}* \theta_{e} \\ %+\overline{\beta}* \theta_{e} * (\overline{\overline{Af_{(t-T_{e})}}} \circ \overline{\overline{\overline{Ih}}})\\ - \overline{O(T_{e}+T_{l})} * \theta_{e} * D(\theta_{l},0) %\prod_{i=1}^{T_{l}} F(\overline{L_{[t-i]}}) %\theta_{l} \] where the first term accounts for larvae surviving one day to the other; the second therm accounts for the eggs that have hatched within the same period of time; and the last term computes the number of larvae that have transformed into pupae.

Adult Stages

We are ultimately interested in calculating how many adults of each genotype exist at any given point in time. For this, we first calculate the number of eggs that are laid and survive to the adult stages with the equation: \[ \overline{E^{'}}= \overline{O(T_{e}+T_{l}+T_{p})} \\ * \bigg(\overline{\xi_{m}} * (\theta_{e} * \theta_{p}) * (1-\mu_{ad}) * D(\theta_{l},T_{p}) \bigg) \]

With this information we can calculate the current number of male adults in the population by computing the following equation: \[ \overline{Am_{[t]}}= \overline{Am_{[t-1]}} * (1-\mu_{ad})*\overline{\omega_{m}}\\ + (1-\overline{\phi}) * \overline{E^{'}}\\ + \overline{\nu m_{[t-1]}} \] in which the first term represents the number of males surviving from one day to the next; the second term, the fraction of males that survive to adulthood (\(\overline{E'}\)) and emerge as males (\(1-\phi\)); the last term is used to add males into the population as part of gene-drive release campaigns.

Female adult populations are calculated in a similar way: \[ \overline{\overline{Af_{[t]}}}= \overline{\overline{Af_{[t-1]}}} * (1-\mu_{ad}) * \overline{\omega_{f}}\\ + \bigg( \overline{\phi} * \overline{E^{'}}+\overline{\nu f_{[t-1]}}\bigg)^{\top} * \bigg( \frac{\overline{\overline{\eta}}*\overline{Am_{[t-1]}}}{\sum{\overline{Am_{[t-1]}}}} \bigg)%\overline{\overline{Mf}} \] where we first compute the surviving female adults from one day to the next; and then we calculate the mating composition of the female fraction emerging from pupa stage. To do this, we obtain the surviving fraction of eggs that survive to adulthood (\(\overline{E'}\)) and emerge as females (\(\phi\)), we then add the new females added as a result of gene-drive releases (\(\overline{\nu f_{[t-1]}}\)). After doing this, we calculate the proportion of males that are allocated to each female genotype, taking into account their respective mating fitnesses (\(\overline{\overline{\eta}}\)) so that we can introduce the new adult females into the population pool.

Gene Drive Releases and Effects

As was briefly mentioned before, we are including the option to release both male and/or female individuals into the populations. Another important thing to emphasize is that we allow flexible releases sizes and schedules. Our model handles releases internally as lists of population compositions, so it is possible to have releases performed at irregular intervals and with different numbers of mosquito genetic compositions as long as no new genotypes are introduced (which have not been previously defined in the inheritance cube). \[ \overline{\nu} = \bigg\{ \left(\begin{array}{c} g_1 \\ g_2 \\ g_3 \\ \vdots \\ g_n \end{array}\right)_{t=1} , \left(\begin{array}{c} g_1 \\ g_2 \\ g_3 \\ \vdots \\ g_n \end{array}\right)_{t=2} , \cdots , \left(\begin{array}{c} g_1 \\ g_2 \\ g_3 \\ \vdots \\ g_n \end{array}\right)_{t=x} \bigg\} \]

So far, however, we have not described the way in which the effects of these gene-drives are included into the mosquito populations dynamics. This is done through the use of various modifiers included in the equations:

- \(\overline{\omega}\): Relative increase in mortality (zero being full mortality effects and one no mortality effect)

- \(\overline{\phi}\): Relative shift in the sex of the pupating mosquitoes (zero biases the sex ratio towards males, whilst 1 biases the ratio towards females).

- \(\overline{\overline{\eta}}\): Standardized mating fitness (zero being complete fitness ineptitude, and one being regular mating skills).

- \(\overline{\beta}\): Fecundity (average number of eggs laid per day).

- \(\overline{\xi}\): Pupation success (zero being full mortality and one full pupation success).

Migration

To simulate migration within our framework we are considering patches (or nodes) of fully-mixed populations in a network structure. This allows us to handle mosquito movement across spatially-distributed populations with a transitions matrix, which is calculated with the tensor outer product of the genotypes population tensors and the transitions matrix of the network as follows: \[ \overline{Am_{(t)}^{i}}= \sum{\overline{A_{m}^j} \otimes \overline{\overline{\tau m_{[t-1]}}}} \\ \overline{\overline{Af_{(t)}^{i}}}= \sum{\overline{\overline{A_{f}^j}} \otimes \overline{\overline{\tau f_{[t-1]}}}} \]

In these equations the new population of the patch \(i\) is calculated by summing the migrating mosquitoes of all the \(j\) patches across the network defined by the transitions matrix \(\tau\), which stores the mosquito migration probabilities from patch to patch. It is worth noting that the migration probabilities matrices can be different for males and females; and that there’s no inherent need for them to be static (the migration probabilities may vary over time to accommodate wind changes due to seasonality).

Stochasticity

MGDrivE allows all inheritance, migration, and population dynamics processes to be simulated stochastically; this accounts for the inherent probabilistic nature of the processes governing the interactions and life-cycles of organisms. In the next section, we will describe all the stochastic processes that can be activated in the program. It should be noted that all of these can be turned on and off independently from one another as required by the researcher.

Mosquito Biology

Oviposition

Stochastic egg laying by female/male pairs is separated into two steps: calculating the number of eggs laid by the females and then distributing laid eggs according to their genotypes. The number of eggs laid follows a Poisson distribution conditioned on the number of female/male pairs and the fertility of each female.

\[ Poisson( \lambda = numFemales*Fertility) \]

Multinomial sampling, conditioned on the number of offspring and the relative viability of each genotype, determines the genotypes of the offspring.

\[ Multinomial \left(numOffspring, p_1, p_2\dots p_b \right)=\frac{numOffspring!}{p_1!\,p_2\,\dots p_n}p_1^{n_1}p_2^{n_2}\dots p_n^{n_n} \]

Sex Determination

Sex of the offspring is determined by multinomial sampling. This is conditioned on the number of eggs that live to hatching and a probability of being female, allowing the user to design systems that skew the sex ratio of the offspring through reproductive mechanisms.

\[ Multinomial(numHatchingEggs, p_{female}, p_{female}) \]

Mating

Stochastic mating is determined by multinomial sampling conditioned on the number of males and their fitness. It is assumed that females mate only once in their life, therefore each female will sample from the available males and be done, while the males are free to potentially mate with multiple females. The males’ ability to mate is modulated with a fitness term, thereby allowing some genotypes to be less fit than others (as seen often with lab releases).

\[ Multinomial(numFemales, p_1f_1, p_2f_2, \dots p_nf_n) \]

Other Stochastic Processes

All remaining stochastic processes (larval survival, hatching ,pupating, surviving to adult hood) are determined by binomial sampling conditioned on factors affecting the current life stage. These factors are determined empirically from mosquito population data.

Migration

Variance of stochastic movement (not used in diffusion model of migration).

References

- Deredec A, Godfray HCJ, Burt A (2011). “Requirements for effective malaria control with homing endonuclease genes.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(43), E874–80. ISSN 1091-6490, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110717108 , https://www.pnas.org/content/108/43/E874.

- Hancock PA, Godfray HCJ (2007). “Application of the lumped age-class technique to studying the dynamics of malaria-mosquito-human interactions.” Malaria Journal, 6, 98. ISSN 1475-2875, doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-98 , https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2875-6-98.

- Marshall J, Buchman A, C. HMS, Akbari OS (2017). “Overcoming evolved resistance to population-suppressing homing-based gene drives.” Nature Scientific Reports, 1–46. ISSN 2045-2322, doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/088427 , https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-02744-7