MGDrivE2: One Node Epidemiological Dynamics - Decoupled SIS Sampling

Source:vignettes/epi-node-SIS-decoupled.Rmd

epi-node-SIS-decoupled.RmdTable of Contents

- Parameterization

- Initialization of the Petri Net

- Equilibrium Conditions and Hazard Functions

- Simulation of Fully Specified SPN Model

- References

Preface

In this vignette, we show a proof-of-concept of a new sampling framework in which the mosquito dynamics are decoupled from the human dynamics. The two systems pass relevant information to each other at time step for the duration of the simulation. The motivation for decoupling the human and mosquito dynamics is to be able to incorporate more complex models of disease transmission into MGDrivE-2’s sampling framework. While this vignette shows a simple SIS model, the eventual goal is to incorporate the Imperial College model of malaria transmission (https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-72317/v1) to model the epidemiological effects of gene drive organisms. This model, alongside other complex models, are not directly compatible with MGDrivE-2’s stochastic Petri net (SPN) architecture due to continuous-state immunity functions and non-Markovian delays, and therefore are separated into their own module. Future vignettes will showcase the decoupled functionality with the Imperial model, but here we showcase the functionality with an SIS model.

In this way, we can still leverage the entomological simulations furnished by MGDrivE-2 and apply the relevant parameters to the epidemiological module. This framework also allows for other models of disease transmission to be swapped in when needed. Here, only the mosquito component functions as an SPN, whereas the human component is formulated using ODEs. For a more complete overview of the decoupled sampling framework, see: https://www.overleaf.com/read/hhwbxpqnhzfv

We start by loading the MGDrivE2 package, as well as the MGDrivE package for access to inheritance cubes and ggplot2 for graphical analysis. We will use the basic cube to simulate Mendelian inheritance for this example.

Parameterization

Several parameters are necessary to setup the structural properties

of the Petri Net, as well as calculate the population distribution at

equilibrium, setup initial conditions, and calculate hazards. Again, we

specify all entomological parameters as for the mosquito-only simulation

(see “MGDrivE2: One Node Lifecycle

Dynamics”) as well as additional parameters for the

SEI mosquito dynamics. Like the aquatic stages,

will give the mean dwell time for incubating mosquitoes, and variance by

.

The model requires muH, mortality rate in humans, because

equilibrium dynamics are simulated (that is, human populations follow an

“open cohort” with equal birth and death rates). A table of

(case-sensitive) epidemiological parameters the user needs to specify is

given below. Note that all parameters must be specified as a rate per

day. For a detailed discussion of these parameters in the context of

malaria models, see Smith and McKenzie (2004).

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

NH |

total human population size |

X |

equilibrium prevalence of disease in humans |

f |

mosquito feeding rate |

Q |

proportion of blood meals taken on humans (human blood index in field literature) |

b |

mosquito to human transmission efficiency |

c |

human to mosquito transmission efficiency |

r |

rate of recovery in humans |

muH |

mortality rate in humans |

qEIP |

inverse of mean duration of EIP |

nEIP |

shape parameter of Erlang-distributed EIP |

Please note that f and Q must be specified;

this is because future versions of MGDrivE2 will

include additional vector control methods such as IRS (indoor residual

spraying) and ITN (insecticide treated nets). In the presence of

ITNs/IRS f will vary independently as a function of time

depending on intervention coverage.

Additionally, we specify a total simulation length of 300 days, with output stored daily.

# entomological and epidemiological parameters

theta <- list(

# lifecycle parameters

qE = 1/4,

nE = 2,

qL = 1/3,

nL = 3,

qP = 1/6,

nP = 2,

muE = 0.05,

muL = 0.15,

muP = 0.05,

muF = 0.09,

muM = 0.09,

beta = 16,

nu = 1/(4/24),

# epidemiological parameters

NH = 1000,

X = 0.25,

f = 1/3,

Q = 0.9,

b = 0.55,

c = 0.15,

r = 1/200,

muH = 1/(62*365),

qEIP = 1/11,

nEIP = 6

)

theta$a <- theta$f*theta$Q

# simulation parameters

tmax <- 250

dt <- 1We also need to augment the cube with genotype specific transmission

efficiencies; this allows simulations of gene drive systems that confer

pathogen-refractory characteristics to mosquitoes depending on genotype.

The specific parameters we want to attach to the cube are b

and c, the mosquito to human and human to mosquito

transmission efficiencies. We assume that transmission from human to

mosquito is not impacted in modified mosquitoes, but mosquito to human

transmission is significantly reduced in modified mosquitoes. For

detailed descriptions of these parameters for modeling malaria

transmission, see Smith & McKenzie (2004) for extensive discussion.

These genotype-specific transmission efficiencies are used in the human

ODE model to determine the rates of movement between susceptible and

infected compartments.

Initialization of the Petri Net

The SEI disease transmission model sits “on top” of

the existing MGDrivE2 structure, using the default

aquatic and male “places”, but expanding adult female “places” to follow

an Erlang-distributed pathogen incubation period (called the extrinsic

incubation period, EIP). Information on how to choose

the proper EIP distribution can be found in the help

file for ?makeQ_SEI().

The transitions between states is also expanded, providing

transitions for females to progress in infection status, adding human

dynamics, and allowing interaction between mosquito and human states.

All of these additions are handled internally by

spn_T_epiSIS_node(). Since only the mosquito portion is

stochastic, the SPN will only include the mosquito states. Human states

will be handled by the sampling algorithm in the form of a deterministic

ODE.

# Places and transitions

# note decoupled sampling is only supported currently for one node.

SPN_P <- spn_P_epi_decoupled_node(params = theta, cube = cube)

SPN_T <- spn_T_epi_decoupled_node(spn_P = SPN_P, params = theta, cube = cube)

# Stoichiometry matrix

S <- spn_S(spn_P = SPN_P, spn_T = SPN_T)Equilibrium Conditions and Hazard Functions

Now that we have set up the structural properties of the Petri Net, we need to calculate the population distribution at equilibrium and define the initial conditions for the simulation.

The function equilibrium_SEI_SIS() calculates the

equilibrium distribution of female mosquitoes across

SEI stages, based on human populations and

force-of-infection, then calculates all other equilibria. We set the

logistic form for larval density-dependence in these examples by specify

log_dd = TRUE.

# SEI mosquitoes and SIS humans equilibrium

# outputs required parameters in the named list "params"

# outputs initial equilibrium for adv users, "init

# outputs properly filled initial markings, "M0"

initialCons <- equilibrium_SEI_decoupled_mosy(params = theta, phi = 0.5, log_dd = TRUE,

spn_P = SPN_P, cube = cube)

# augment with human equilibrium states

initialCons$H <- equilibrium_SEI_decoupled_human(params = theta)With the equilibrium conditions calculated (see

?equilibrium_SEI_SIS()), and the list of possible

transitions provided by spn_T_epiSIS_node(), we can now

calculate the rates of those transitions between states.

# approximate hazards for continuous approximation

approx_hazards <- spn_hazards_decoupled(spn_P = SPN_P, spn_T = SPN_T, cube = cube,

params = initialCons$params, type = "SIS",

log_dd = TRUE, exact = FALSE, tol = 1e-8,

verbose = FALSE)Simulation of Fully Specified SPN Model

Similar to previous simulations, we will release 50 adult females

with homozygous recessive alleles 5 times, every 10 days, but starting

at day 20. Remember, it is critically important that the event

names match a place name in the simulation. The simulation

function checks this and will throw an error if the event name does not

exist as a place in the simulation. This format is used in

MGDrivE2 for consistency with solvers in

deSolve.

# releases

r_times <- seq(from = 20, length.out = 5, by = 10)

r_size <- 50

events <- data.frame("var" = paste0("F_", cube$releaseType, "_", cube$wildType, "_S"),

"time" = r_times,

"value" = r_size,

"method" = "add",

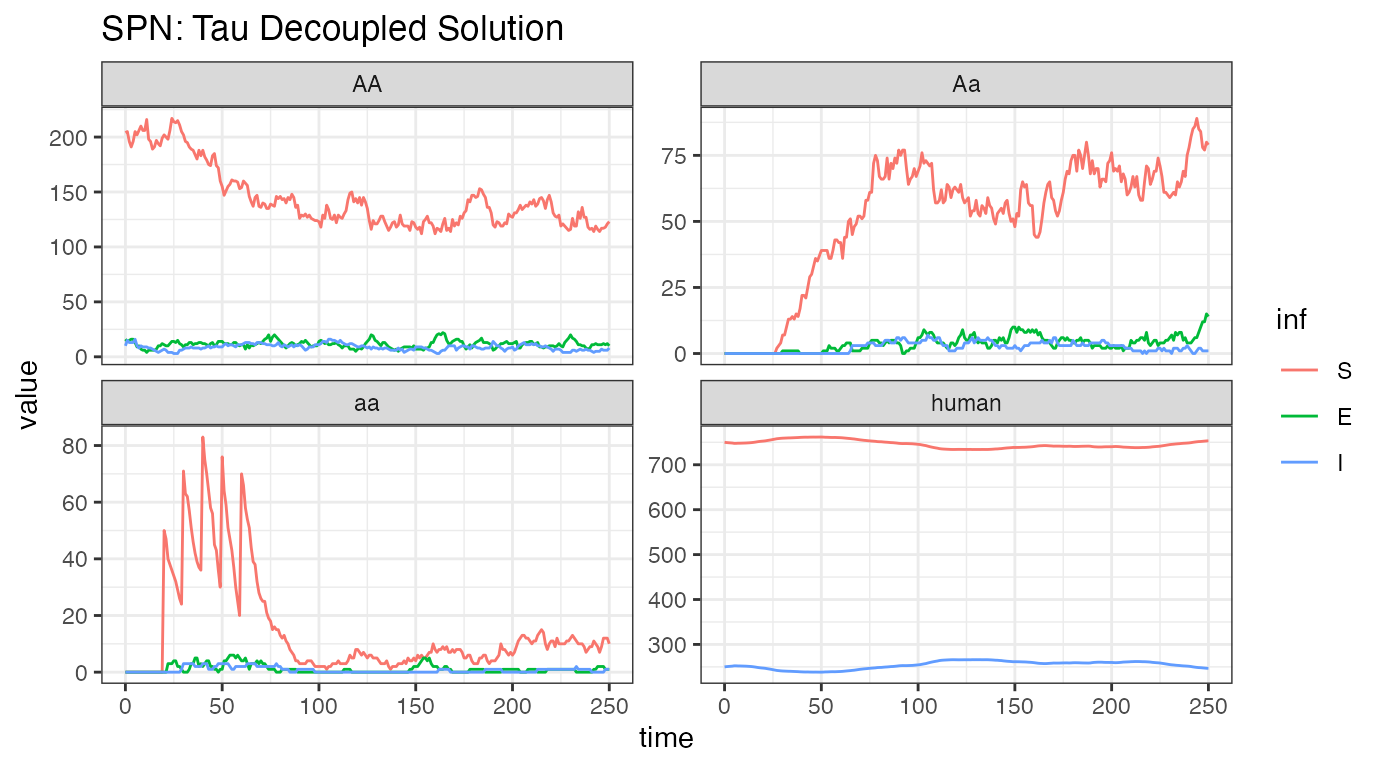

stringsAsFactors = FALSE)Stochastic: Tau Leaping Solutions

As a further example, we run a single stochastic realization of the

same simulation, using the tau-decoupled sampler with

,

approximating 10 jumps per day. This means that we use a tau-leaping

sampler in the mosquito states’ SPN, and ODE integration the human

model. As the adult male mosquitoes do not contribute to infection

dynamics, we will only view the adult female mosquito and human dynamics

here.

# delta t - one day

dt_stoch <- 0.1

# run tau-leaping simulation

tau_out <- sim_trajectory_R_decoupled(

x0 = initialCons$M0,

h0 = initialCons$H,

SPN_P = SPN_P,

theta = theta,

tmax = tmax,

inf_labels = SPN_T$inf_labels,

dt = dt,

dt_stoch = dt_stoch,

S = S,

hazards = approx_hazards,

sampler = "tau-decoupled",

events = events,

verbose = FALSE,

human_ode = "SIS",

cube = cube

)

# summarize females/humans by genotype

tau_female <- summarize_females_epi(out = tau_out$state, spn_P = SPN_P)

tau_humans <- summarize_humans_epiSIS(out = tau_out$state)

# plot

ggplot(data = rbind(tau_female, tau_humans) ) +

geom_line(aes(x = time, y = value, color = inf)) +

facet_wrap(~ genotype, scales = "free_y") +

theme_bw() +

ggtitle("SPN: Tau Decoupled Solution")

Analyzing one stochastic realization of this system, we see some similarities and some striking differences. The releases are clearly visible, lower left-hand plot, and we see that the initial dynamics are similar to the ODE dynamics. However, it is quickly apparent that the releases are not reducing transmission adequately, that in fact, disease incidence is increasing rapidly in human and female mosquitoes. There are two main possibilities for this: first, that the stochastic simulation just happens to drift like this, a visual reminder that there can be significant differences when the well-mixed, mean-field assumptions are relaxed, or that the step size () is too large, and the stochastic simulation is a poor approximation of the ODE solution. Further tests, with and , returned similar results, indicating that this is an accurate approximation but still highlighting the importance of testing several values of for consistency.